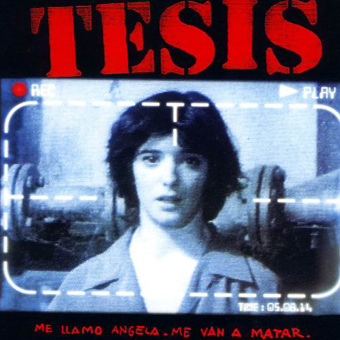

Therefore, it is possible to argue that government funding would in fact be put to much better use by investing in digital theatres and decreasing film subsidies. Once digital exhibition is in place, natural market economics and the inherent savings of digital production will force the industry to follow suit. This switch will allow the presently cosseted market to save money on every film genre, thus allowing market economics and audience preference to dictate what is produced, instead of the government. Film popularity and box office revenue must be considered along with cultural significance if Spanish films are to avoid becoming mere ciphers to an American-dominated market. As Xabier Elorriaga's character ominously states in Alejandro Amenábar's dark debut feature, Thesis ( Tésis , 1996): ‘We've reached a critical stage. Our cinema won't be saved unless it's understood as an industrial phenomenon. Out there the American industry is trampling you and there's only one way to compete: Give the public what it wants to see.'

To this end, one option that the government has is to begin installing a combination of D-cinema and E-cinema projectors. The Chinese government chose this route, announcing plans to roll out both types of projectors, 2,500 in total, over the next five years. The UK Film Council is allocating £13 million (US$21 million) for the installation of 250 cinema-quality projectors across the country. Regal's Cinemedia Digital Network has 4,700 low-end projectors installed in 394 theatres in the USA . Other governments around the world are discovering the potential profits offered by digital exhibition, and are beginning to invest as well.

Film subsidies need not be eliminated, but should serve as a component of an economically viable industry, not as its lifeline. One suggestion, promoted by José María Caparrós Lera, a Spanish film historian and director of the Film-Historia Centre for Cinematic Research in Barcelona , is to give subsidies only to first time directors, thus giving them an opportunity to succeed in the market, but demanding that personal talent and directorial success determine their future.46 Additionally, the government should allow these subsidies to go to digital productions, a format they do not currently cover.47

Aside from digital projectors and subsidies, the government could also invest in the training of current cinematographers in the operation of digital cameras. Sergi Maudet, the HD manager at Ovide BS, a leading Spanish camera rental company, has seen a large increase in HD rental for television productions (25 per cent in 2003), but little in film. He attributes this partially to the more established use of HD for television, but also to the unfamiliarity of filmmakers with digital systems.48 A positive step in this direction has been the creation of a series of digital film workshops by the eminent Spanish director Bigas Luna , an outspoken proponent of the digital medium. In an effort to open up the world of production to young filmmakers, he has recently led several small workshops, of about 20 students each, in order to teach them not only about digital cameras, but also about the art of storytelling in the digital age. The students are taught to use the cameras, and are given the opportunity to assist in filmmaking. ‘One [of my trainees] has already signed a contract with a producer who finances the films of my most promising students. That's part of what I'm trying to do – help young filmmakers with their own projects.'49 If more directors and camera operators become familiar with digital cameras, this will ease the transition to digital filmmaking. The government could assist in this area by offering subsidies for courses in digital camerawork, or for digital equipment purchases. Although the MEDIA and Eurimages programs mentioned earlier can be faulted for the same intervention as the individual European states, their subsidizing of training programs and promotion of new technologies is a step in the right direction.

There is no doubt that the traditional film industry is transforming, and the probability that digital platforms will eventually become the worldwide norm for filmmaking is high. This will offer advantages to everyone from Hollywood studio executives to documentarians in the Amazon. However, when each country chooses to adopt these changes, and how much each will benefit from them, varies enormously. The countries that have the most to gain from the conversion are those with prolific film industries dominated by low and medium budget films. Encouraging digital filmmaking will save money for established filmmakers, and will open up the market to new ones.