Introduction

For decades, filmmakers around the world have fought tirelessly against the inexorable force of the American film industry. Countries that attempt to establish an audience for their own national cinema are constantly battling the Hollywood juggernaut, and trying to reshape their own industry to promote domestic product both at home and abroad. In many West European countries, the effort has been only partially successful. American films continue to dominate the box office, and a recent increase in the home video and television markets have lowered theatre attendance across the board.

New digital film technologies, such as digital cameras and projectors, have been some of the latest additions to the ever more complicated world of production. They have provided new options for players on every level of the filmmaking process, but have also posed new challenges and inspired highly politicized debates. Both supporters and detractors of digital film question whether these technologies have any real potential for improving the playing field for national filmmakers. In Europe, many professionals within the industry do not fully understand the possibilities offered by these new options, and few have risked experimentation.

‘Celluloid is dead. Long live film' was the prophetic declaration of Francis Ford Coppola at the 2002 San Sebastian Film Festival in Northern Spain , where he was honored with a Lifetime Achievement award.1 But although many directors, such as Coppola and George Lucas, have espoused the digital revolution, the changes have not fully materialized in Europe , and are virtually nonexistent within Spain . Although digital post-production (editing, image manipulation, and special effects) has existed in Spain for some time, the sectors of production, distribution, and exhibition are lagging behind much of the rest of the world in testing these new technologies.Digital systems make savings possible at every step of the production process, and in some cases provide new sources of income. In a country like Spain that is flooded with low budget features and suffers from poor distribution, these concerns become very important. This article examines the potential benefits of digital technologies to Spain 's struggling film industry.

The legacy of Franco

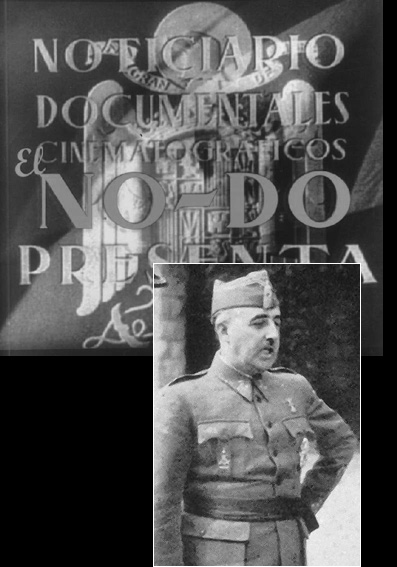

The attempt to create an indigenous commercial film industry in Spain is not new. The Spanish government reached a peak of active involvement in film during the fascist regime of General Francisco Franco (1936-1975), and the systems put in place by his government have left an enduring mark on the audiovisual sector. Ironically, Franco put more of a focus on the development of the film industry than any previous government, and yet at the same time enforced laws that would severely hamper its potential for commercial and critical success. Instead of viewing cinema as an artistic or fiscal matter, Franco saw only its potential as a propaganda machine. He even went so far as to write his own novel and have it turned into a self-aggrandizing war film. Although there were certainly worthwhile films produced during the period, the effort to revitalise the industry ultimately failed because creativity was painfully stifled.

Numerous attempts by directors to create controversial or thought-provoking films were thwarted by arbitrary story modifications and draconian censorship laws. Variously named film classification and censorship boards dictated how directors presented Spain in their films, while government-controlled monopolies such as ‘No-Do' 2 carefully monitored what the public saw and understood of the outside world. Gifted filmmakers, such as Luis Buñuel, were forced to leave Spain in order to work freely. And of course, even if their films became successful abroad, they were not permitted to be seen by Spanish audiences.

The strict monitoring of national and international releases backfired, however, by reducing the popularity of Spanish films. Two particular laws imposed by the regime weakened the national film industry by strengthening the status and appeal of foreign films. The first, passed in 1941, called for the compulsory dubbing of foreign language films into Spanish. Its purpose was to avoid the adulteration of the Spanish language by foreign vernacular, and to promote the national language within Spain itself (regional languages, such as Catalan and Basque, were also dubbed). Although the law was repealed in 1947, dubbing has now become the standard for foreign films, making them even more accessible to the Spanish film audience and relegating any subtitled films to the art-house circuit. The accepted practice in the USA of subtitling all foreign language releases has similarly limited their popularity to a small niche market.

The second law involved the system by which foreign films were imported. In order to distribute foreign films, producers had to obtain permits. In order to receive such permits, they had to first release a Spanish film. Although a seemingly logical method of protecting their indigenous industry, the allocation of permits was cleverly tied to a ‘classification' system, whereby Spanish films which served to promote the regime received higher classifications. The higher the ‘classification' given to a Spanish film, the more permits to import foreign films the producer was allocated. Since audiences preferred American films, this system frequently resulted in indigenous films becoming no more than ‘conventional vehicles for fascist mythology'.3 Although a number of directors, such as Juan Antonio Bardem, Luis García Berlanga and many of the ‘Nuevo Cine Español' directors, managed to avoid this pitfall with some of their films, it required not only a passion to create films that broke with that tendency, but also the ability to make it past the censorship boards.

After Franco's death in 1975 and the full repeal of censorship laws in 1977, the desire to examine the realities of Spanish social and political life flourished again. This time, however, films could be made about formerly taboo topics, such as homosexuality, drugs, and divorce. Although this was initially an exhilarating time for directors, the Spanish film industry was quickly debilitated by the rapid increase in television ownership in the 1970s, and subsequently by the global recession of the early 1980s. Moreover, foreign films which had been banned during the Franco years were suddenly available, and Spanish audiences were more than eager to see them.

By 1978, 80 per cent of Spanish film professionals were unemployed 4 and theatre attendance soon declined, with the number of cinema screens falling from approximately 5,000 to 3,500 between 1972 and 1982. 5 Spain 's entry into the European Community in 1986, coupled with a steeper rise in the number of television-owning households in the late 1980s augured an even worse state of affairs for traditional cinema. By 1990 only 1,802 screens remained open, and Spain had to compete with the European films that now flowed ever more freely across its borders. In 1989, despite efforts to promote the industry, producers released a paltry 47 films.6

Current state of the industry

Due to a growing economy and an increase in film subsidies, production has since risen. According to the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), the number of films released in Spain has increased steadily every year since 1998, reaching a 20-year record in 2002 with the production of 137 films.

Unfortunately, approximately 10 per cent of these were never screened,7 and 70 per cent lost money.8 This is partially due to the popularity of American films, which took 67.2 per cent of the box office market share in 2003, while Spanish films received only 15.8 per cent.9 Of the five major film-producing countries of Europe that year,10 only the UK 's national market share was lower than Spain 's.11

Those in the industry lay the blame for these figures variously on the Spanish government, the production companies, and the influence of Hollywood , but the search for a scapegoat has only exacerbated and prolonged the problem. In an attempt to improve the state of the industry, the ICAA ( Institute of Cinematography and Visual Arts) was created in 1984 to address some of these issues. Among their stated goals are an increase in the production of Spanish films, a greater national market share, and the creation of incentives for the take-up of digital technologies.12 However, while the first goal has been accomplished, the ICAA is not making sufficient efforts to advance the latter two. The agency's principal activity lies in distributing grants to filmmakers. In 2002, the state government gave a total of €40.8 million to the audiovisual sector, with about €30 million being allocated to the production of 71 films. On average these films received 23 per cent of their budget from the state.13 In addition to the production subsidies, another law, inspired by similar measures in France and Italy , gives each producer 15 per cent of the box office return on his or her film for the first year after its release. 14 But while this grant is given to every producer, the production grants are awarded based on each film's ‘cultural merit', which – according to the MEC – means how the film presents Spain to the outside world. Such films should offer ‘an expression of [ Spain 's] personality and its history, forming a part of the country's identity'.15 This vaguely worded requirement, written into law, may sound eerily reminiscent of the days of Franco, but is standard policy for the rest of Western Europe as well. Cultural promotion is seen throughout the region as the best way to keep European cinema alive in the face of the Hollywood juggernaut.

Despite the benevolent intentions of the board, however, these grants have created a reliance by filmmakers on the largesse of the government, a disincentive to find independent financing, and a limited range of genres. Likewise throughout Europe , state governments dictate which films deserve to be funded, and thus influence production. Director, media consultant, and industry critic Martin Dale states: ‘Culture is the “holy of holies” of the European power system, and ever since the days of Louis XIV, subsidies have been used by the state to encourage certain national authors and discourage others.'16 This has unfortunately not had the hoped for outcome. Many Spaniards view homegrown cinema as low-grade, and consistently opt for foreign, usually American, fair. The consequent attempt to balance cultural promotion and financial viability has produced one of the industry's most impassioned struggles. If Spain is to escape the stranglehold resulting from the perceived inferiority of its films and the government constraints on production, it must find a way to increase both the critical and box-office success of its films. Digital technologies offer the opportunity to modernize the industry, bringing with it financial savings and easier distribution, which in turn offer the possibility of not only increasing revenues, but also widening the reach of Spanish cinema.